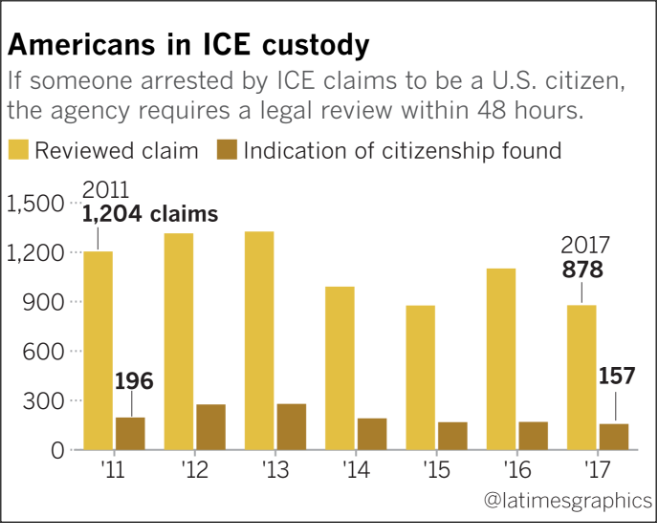

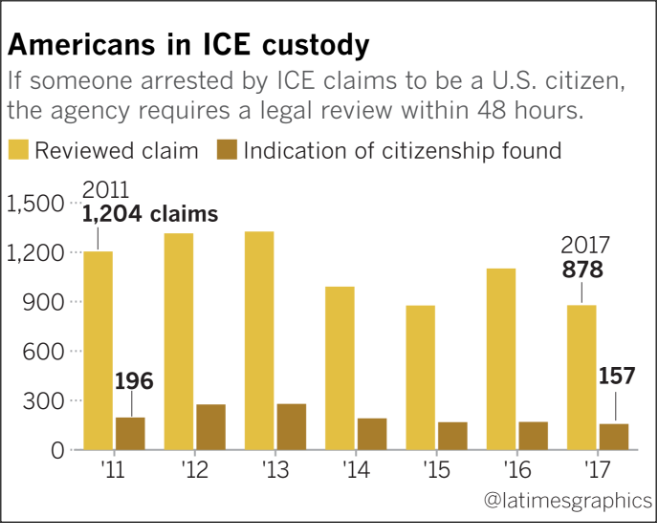

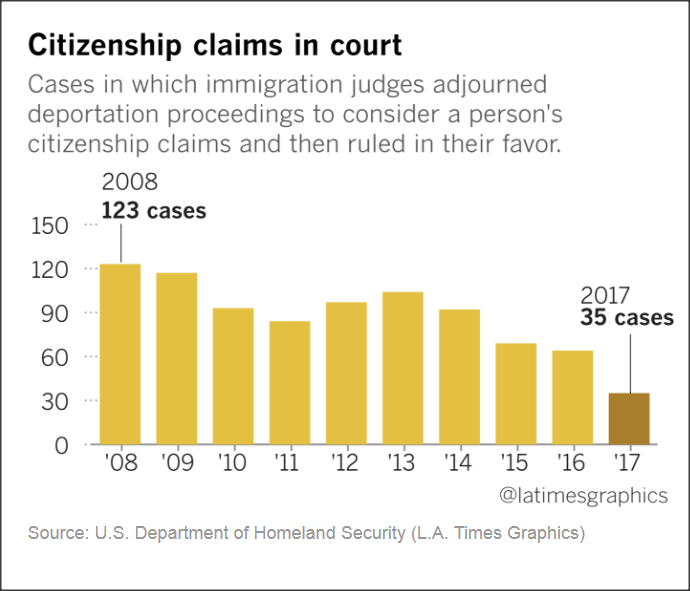

GRAPHIC ON ICE REVIEWS OF U.S. CITIZENSHIP CLAIMS

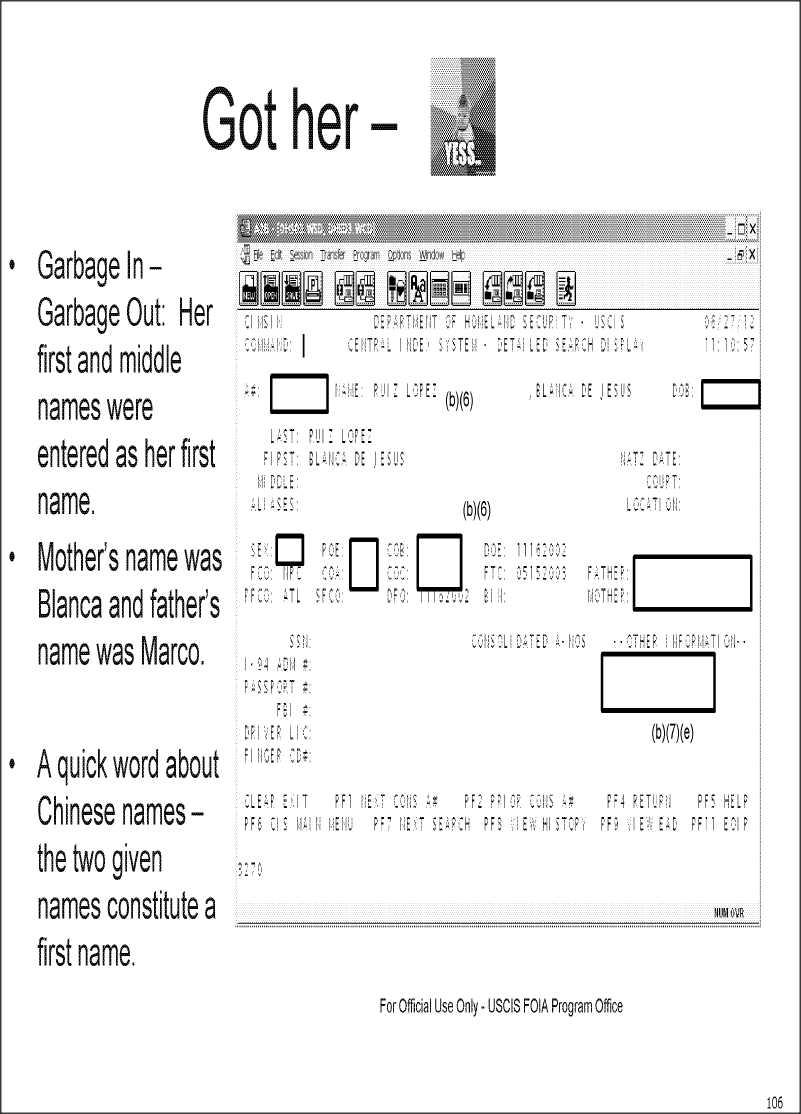

A training document for users of the Central Index System, which is maintained by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, warns of incorrect or multiple identification numbers, scrambled names, inconsistent procedures for recording multi-part names common in Latin and Chinese cultures, aliases, misspellings and typographical errors, incorrect birth dates and lost records.

“Garbage in, garbage out,” the document cautions, a reminder that what computer systems deliver is only as good as what goes in.